The Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 2, Verses 1 ... 4

Gita Post #13

An Introduction to Chapter 2

The title of this chapter is Sāṅkhya Yoga. Sāṅkhya Darśana, not the Sāṅkhya Yoga spoken of in the Bhagavad Gita, is a philosophy that had existed in India, presumably, before the Upanishadic teachings called Vedanta became available as the ultimate in philosophy. The authorship of the original Sāṅkhya Darśana is ascribed to Sage Kapila. The emergence of Vedantic wisdom was the culmination in the evolution of Indian Philosophy. The word Vedanta means the finality (anta) of knowledge (veda). To understand in another way, the Upanishads are the concluding sections (anta) of the Vedas (therefore Vedanta), so initially Vedanta meant the Upanishads and later, Vedanta denoted the common philosophy across all the Upanishads expounded by other texts such as the Bhagavad Gita as well.

The multiplicity of Reality (called purusha in Sāṅkhya Darśana) talked about by the Sāṅkhya philosophy is its major difference over Vedanta. While Śaṅkarāchārya’s Advaita interpretation of the Upanishads establishes the non-duality of Reality in Vedanta philosophy, the Gita Dhyāna (Meditations on the Gita), usually prefixed by publishers along with the text of the Bhagavad Gita, also has its first verse saying the Gita is *advaitāmṛta-varshiṇi (that which showers the nectar of Advaita or non-duality). The Vedantic texts consider only one ultimate Truth called Brahman or Purushottama (a Gita term). Vedanta has otherwise many parallels in the Sāṅkhya exposition of the cosmic principles. Sage Vyāsa adopts the term Sāṅkhya, not the philosophy as it is, in the Bhagavad Gita.

[*ॐ पार्थाय प्रतिबोधितां भगवता नारायणेन स्वयं

व्यासेन ग्रथितां पुराणमुनिना मध्ये महाभारते

अद्वैतामृतवर्षिणीं भगवतीमष्टादशाध्यायिनीं

अम्ब त्वामनुसन्दधामि भगवद्गीते भवद्वेषिणीम्

Aum pārthāya pratibodhitām bhagavatā nārāyaṇena svayam

vyāsena grathitām purāṇamuninā madhye mahābhārate

advaitāmṛta-varshiṇīm bhagavatīm-ashṭādaśādhyāyinīm

amba tvāmanusandadhāmi bhagavad-gīte bhavadveshiṇīm]

The method of the Sāṅkhya philosophy to find Reality is one of 'knowledge through reasoning'. Sage Vyāsa has adopted the term Sāṅkhya in the Bhagavad Gita and employed it to signify the Vedantic method (path) of knowledge (jñāna), followed by a section of the seekers. To the author of the Bhagavad Gita, those seekers are of Sāṅkhya buddhi. [Although buddhi stands for intelligence, in the present context it means the seeker’s firm understanding arrived at, by rational discrimination, in the search for Reality.] Sāṅkhya buddhi is indicated by the seeker’s unshakable conviction about the one and only eternal Reality, which is beyond ordinary human perception. The corollary is that the phenomenal world is non-Real and transient. Śaṅkarāchārya calls this firm-standing understanding nityā-anitya-viveka (discrimination between the eternal and the transient). There is an impression carried by the public that the seekers who are of Sāṅkhya buddhi (following the path of jñāna or knowledge) altogether renounce work and actions; in fact a criticism also exists against Vedanta that it advocates inaction or passivity. The study of the Yoga Śāstra of the Bhagavad Gita obviates any such misgivings.

The Yoga system of Patañjali has essentially a practice-based method of realizing Truth. The Bhagavad Gita adopts the term Yoga to denote the method that helps attain Reality even when the seeker remains engaged in regular works and actions (karma). In this chapter, the path of karma taught by the Gita is termed Yoga; in Chapter 3, it is renamed karma yoga. The seekers following the path of karma, the Gita says, are of Yoga buddhi [here buddhi is the profound understanding of the work and actions (karma) one does ̶ that understanding is the sum of all the awareness such as (a) what karma is, (b) the right disposition of the individual while engaged in karma, (c) the knowledge of who the owner of karma and the results or profit it brings is].

Here, a restatement of Vedanta philosophy begins. The author explains an integral method that accomplishes a synthesis, by incorporating the adoptable principles appropriate for Vedanta, of the other two systems (Sāṅkhya and Yoga) into the Bhagavad Gita.

Later in this chapter itself, the Sage brings out that the search for Reality works well only when Sāṅkhya buddhi (of knowledge or jñāna) and Yoga buddhi (of works and actions ̶ karma) operate together in a seeker. It means the two kinds of buddhi [firm understanding established by discrimination] have to be in a state of yoga (inseparably amalgamated), forming a unique single understanding. The seeker who has those two kinds of buddhi merged into one in this fashion is said to be in a state of buddhi-yoga. [The Sanskrit, the word yoga has yuj as its root; yuj means to join or unite.] Kṛshṇa asserts that one who practices buddhi-yoga will attain samādhi (the transcendental mystic state of Yogis).

This chapter thus provides an abstract of the entire yoga śāstra of the Bhagavad Gita, which is elaborated systematically in the later chapters.

[Everything in the Bhagavad Gita is 'devised' in a method of yoga, which is a striking specialty of this scripture ̶ from the synthesis of simpler concepts to the subtlest dialectics of the ultimate Reality. The language employed in the Gita is no exception. In a masterly way, the dire need to restore righteousness in an already hopeless world of adharma (unrighteousness) and the path to the supreme knowledge of the Absolute are embedded always in the same words and statements in the Gita; those two aspects are synthesized in the language of the Gita; or, yoga of concepts and doctrines is realized through its language. For that reason, interpreting the text of the scripture involves a reverse process through contemplation. This aspect poses an enormous challenge to the adaptation of any common interpretations of the Gita statements, and more so for Chapter 2. Therefore, we notice that no two serious commentaries on the Gita agree on interpretations, occasionally leading to confusions even about the basic Vedantic principles. It is important for us to keep this reality in mind when we progress with the study of this sublime hymn of Yoga Śāstra.]

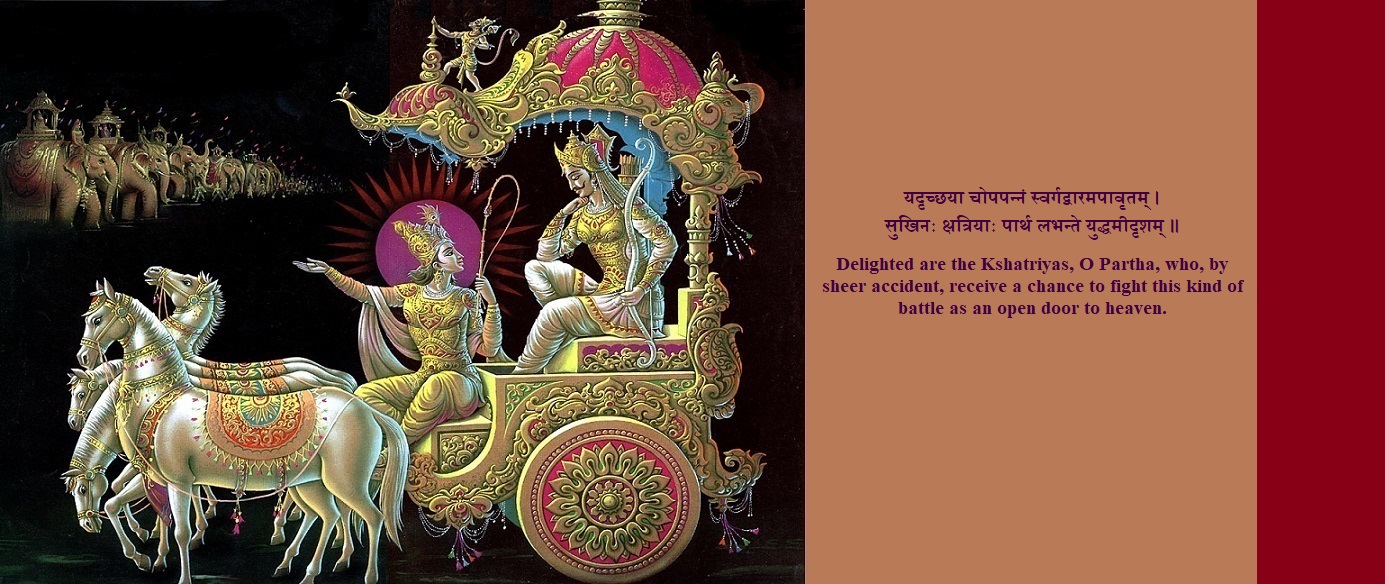

Let us now continue with our svādhyāya. Arjuna, immobilized by the mysterious force of para, sits inactive in his chariot while the battle picks up momentum. “It will be a blessing for me if the sons of Dhṛtarāshṭra, with weapons in hand, should kill me while I stay unarmed and unresisting in the battle,” Arjuna has said, before he has decidedly withdrawn himself from the battle.

Arjuna, like every one of us, is an individual. In the Gita language, he is a dehi (embodied Ātman). We do not realize the presence of Ātman in the body because of the ‘external stuff’ that is accumulated in the body-mind complex. In other words, the mind is ‘conditioned’ by the interactions with the world; such a mind acts as a hindrance to the awareness of our true nature, Ātman.

Arjuna represents all of us. What Kṛshṇa is about to teach him is for the sake of the entire humanity. Arjuna faces the world (jagat). Everything outside him is the world. The world is full of objects of different kinds. His sense organs are always in contact with the objects and keep giving feedback to the mind. The mind, with the assistance of intellect, makes decisions discriminating between the objects it likes and dislikes. Then the next question is how to own the objects of liking and avoid the others. In this process, the individual encounters numerous problems of different scales, causing perpetual conflicts and confusions, even in the subconscious mind.

We have thus seen two factors: the individual and the world. There is a third factor ̶ Brahman, the Absolute. The position of the Absolute is neutral, neither on the side of the individual nor on that of the world.

So abrupt has been the ‘act’ of para on Arjuna that the natural defence mechanisms of the body have remained ineffective. As he goes through the experience, a shockingly terrific force pulls him to move towards the neutral position of the Absolute (Brahman), where there are no desires and the consequent conflicts and confusions. But Arjuna lands in a new conflict that thoroughly confuses him; all the distress symptoms Vyāsa describes are owing to the new conflict. He came prepared for the battle, but the pull by the Absolute stops him with brute force. He is overwhelmed by the compassion that is typical of the domain of the Transcendental (para). But his mind, already conditioned by the worldly experiences, has made him a thoroughly confused man. The ‘link’ between para that has generated the compassion and the world of desires is dormant in Arjuna. It is the wisdom of the Absolute, to be gained by buddhi-yoga.

From the point of view of Vedanta, Arjuna represents the individual (vyashṭi); the two armies of four million soldiers he surveys from the centre of the battlefield represent the world (samashṭi); and the unarmed Kṛshṇa is the Absolute (Brahman) staying in the neutral position as a witness (sākshi).

We are in the Bhagavad Gita section of the Mahābhārata and eager to hear the teachings of the Jagad Guru, Bhagavan Kṛshṇa, but there has to be a compelling reason for the Guru to teach. And that reason is usually the irresistible urge of a disciple to know, to gain the supreme wisdom. (Otherwise, Kṛshṇa will remain the charioteer and friend of Arjuna.) Early in this chapter, the poet creates such an urge in Arjuna, the hero of the world, who otherwise has displayed no spiritual inclination at any point in his life. The first two chapters of the Bhagavad Gita thus exemplify the inestimable creative genius of the Sage in making the impossible a simple-looking possibility!

Translation

Sanjaya said: Slayer of Madhu (Kṛshṇa) spoke these words to him (Arjuna), who is overcome by compassion, anguished and grieving, with eyes full of tears.

Annotation

In Chapter 1, we have noticed that the kṛpa (compassion) that overpowers Arjuna is certainly not an ordinary emotion, but one beyond all normal human emotions—of transcendental nature. Vyāsa has clearly mentioned the kṛpa (compassion) he feels is because para has seized him (parayā āvishṭaḥ). When under the influence of para, one does not distinguish people based on factors such as relatives and non-relatives; all are of equal value. Being the manifestations of the one common Self (Ātman), all the soldiers assembled on the battlefield appeared to Arjuna as his own people (svajanaḥ). It is more important to know that he finds everyone non-different from himself. Anything that hurts them would hurt him too. On the other hand, the soft feelings one develops owing to worldly attachments treat people with differentiation. Soon will we notice that Arjuna himself vacillates between the transcendental and the worldly states, because his mystical experience is a momentary (kshudra) one.

Imagine what the experience of Kṛshṇa would be. He has entered the battlefield as Arjuna’s charioteer. His job is only to drive the chariot skilfully when Arjuna engages himself in the battle. Now Kṛshṇa has nothing to do, which looks absurd (to us)! Bhagavan speaks.

Translation

Sri Bhagavān said: O Arjuna, at this critical point, where from has come upon you this untimely dejection becoming only for unworthy people? It is heaven-barring and brings only disgrace and bad name.

Annotation

Bhagavan Sri Kṛshṇa is always seen with a trace of a smile on his face. He says, “Hey Arjuna, don’t you know you are already at a difficult juncture? A war is a serious affair. You have a crucial role to play now, right here; and you are making a fool of yourself when the opportunity is before you to show your bravery, honor and discernment! This behavior is expected only of unworthy people. Oh, you have said you wish to live in heaven; do you think such behavior will help you fulfil your ambition? This conduct of yours is disgraceful and will bring you only a bad name.”

We get a shock by listening to these words of Kṛshṇa, for we start reading with the expectation of getting something very thought provoking from Bhagavan’s opening words. But let us remember Kṛshṇa at this instant is not a guru nor Arjuna is a disciple. He is not only Arjuna’s charioteer, but his cousin and best friend. Kṛshṇa’s sister, Subhadra, is married to Arjuna. Being the bosom friend of Arjuna, Kṛshṇa has all the freedom to chide him. Arjuna will understand he does it out of sincere love. But Kṛshṇa is clever to target Arjuna’s ego so that he soon regains his presence of mind.

We saw in Chapter 1 that Arjuna was profoundly shaken by the unexpected experience of para. In this verse and the one that follows, Kṛshṇa gives him a counter-shock to neutralize the effect of the earlier shock. We may recognize Kṛshṇa’s immediate effort is to get Arjuna out of the jolt that has thrown him out of balance.

Noteworthy is an important phrase used by Kṛshṇa: at this critical point [vishame (विषमे)]. In a relative sense, we have every reason to interpret it as the war situation. We soon will find that there is a deeper meaning implied in all these words of Kṛshṇa .

Let us listen to what Kṛshṇa says next.

Translation

Do not yield to this ignominious impotence, O Partha (Arjuna). It does not befit you at all. Rid yourself of the petty weakness of heart and stand up, O Nightmare of enemies.

Annotation

Kṛshṇa continues to admonish Arjuna. Do we not hear Bhagavan’s voice to mean? “Do not yield to such eunuch-like impotence. Compassion of this degree is good. But do you think you have transformed altogether to be an ever compassionate saint? Then you would be neither grieving nor inactive. I am sure the limitless love and compassion you feel at present is a petty weakness of heart, because it is momentary (kshudram), and will disappear soon. While sitting like a coward, you are ignorant of what you lose. What is becoming for you is to stand up like a conqueror and win what you aspire to.”

[The word klaibyam (क्लैब्यं) literally means eunuch-like impotence. As shown in the word meaning, kshudram (क्षुद्रम्) also means passing or short-lived. Kṛshṇa says Arjuna’s kind-heartedness is kshudram.]

The remarks that Arjuna’s kind-heartedness is kshudram (momentary) and it is only a weakness of heart do contrast the abiding compassion we see as the striking quality of a yogi.

Kṛshṇa appears to be disapproving of Arjuna’s state of dejection and sitting inactive, so asks to stand up. He does not like a vibrant hero of Arjuna’s stature sitting emasculated at the critical point [vishame (विषमे)], yet he is not asking him to lift his bow, Gāndīva. Kṛshṇa seems to mean this is the critical point of his life itself, so he is keen to provoke Arjuna so that his body, mind and spirit wake up from the stupor caused by the transcendental jolt.

Bhagavan’s voice seems full of reproach, but the measured words convey subtly how kind and caring he is.

Parantapa (परन्तप), the epithet Kṛshṇa uses to address Arjuna, means the scorcher of enemies. This is a message that the time to demonstrate his gallantry before his true enemy has come.

Let us see what reaction these words elicit from Arjuna.

Translation

Arjuna said: O Madhusūdana (Kṛshṇa), in this battle, how will I fight with arrows against Bhīshma and Droṇā who are worthy of worship, O Arisūdana (Kṛshṇa)?

Annotation

Here, the way Arjuna addresses Kṛshṇa is significant. He would have intended to mean, “Kṛshṇa, you had to slay only enemies of the worst evil traits who threatened the integral welfare of the world. And you are the All-controller of the universe. [Those killings were symbolic of the triumph over the evil traits that stood against the attainment of śreyas. The Gita later elaborates on such evil traits ̶ āsurī sampatti.] My insurmountable challenge is to fight and kill people who are worthy of worship!”

In Arjuna, we detect a marked effect of Kṛshṇa’s reproachful words. In Chapter 1, we have seen him lamenting over his unfortunate decision to decimate his own people (svajanaḥ), standing everywhere on the battlefield. To avoid the massacre of svajanaḥ, he has contrived to produce reasons such as the destruction of family morals, mixing of castes (varna saṅkaraḥ), the fall of the ancestors from heaven and the entire family becoming destined to live in hell. Kṛshṇa’s stinging rebuke has done the magic. Arjuna senses something incongruous in his arguments, so he is quick enough to re-adjust the reasons and make them sound more sensible. He speaks as though he had only one concern: Bhīshma and Droṇā are revered teachers (gurus) to the Kuru family; they are worthy of worship; how will I kill them?

This should be the psychological impact intended by Kṛshṇa; Arjuna’s thinking faculty begins to function.

--------------------

(To read the next post [Gita Post #14] click/tap on this link: https://www.ekatma.org/node/193)

Leave a comment