The Bhagavad Gita:The Soul of the Mahābhārata - Part I

[Gita Post #1]

One of the fundamental texts of Vedanta is the Bhagavad Gita. It is also the most adored wisdom teaching scripture in India. In a strict sense, the Bhagavad Gita is not a standalone text. The ancient Indian sage Vyāsa wrote the Itihāsa (epic) called the Mahābhārata. The epic is a masterly composition of a saga based on the historical backdrop of a royal dynasty of his time. In the first half of the Itihāsa, a discerning critic will find, in hindsight, a precise build-up to an instructional session on the doctrine of Vedanta. The poet then depicts a brilliant dramatic scene of a dialogue between the two most impressive characters in the story ̶ Kṛshṇa and Arjuna. The part of the epic where the instruction takes place is the Bhagavad Gita; or the Gita, as people prefer to call. In the Mahābhārata, the Sage revalues and restates the philosophy of the Upanishads, which is of eternal relevance to humanity.

Yet, most commentators on the Bhagavad Gita considered it a standalone treatise. The Gita does contain the full treatment of the doctrine it teaches. Even then, its study detached from the epic will make it harder to decode many finer aspects of the scripture. Here, the Gita dialogue takes place at the climax of a well-plotted epic story. And the story describes all along principles that explain the Gita teaching better. In reality, it is the inextricable soul of the epic. The surgical separation of the Gita will sever the threads that connect it to many relevant principles presented in the Mahābhārata. Therefore, ignoring this linkage may cause many Gita verses to look harder to understand. They often sound paradoxical. The readers will thus find it an esoteric treatise.

The Mahābhārata, a Canvas for the Upanishadic Wisdom Teaching

Kṛshṇa-Dvaipāyana Vyāsa1 classified and compiled the Vedas, so he is Veda Vyāsa. The Sage wrote the Mahābhārata to expound the Upanishadic wisdom using a vast canvas of an epic story. In the Mahābhārata, he identifies himself as its author. We read in the very first chapter of the Mahābhārata ̶ Ādi Parva, verse 18, “…the most eminent narrative amongst all narratives, adorned by the essence of the Vedas and their subtle import presented with scientific logic, employing exquisite diction in every section…” “The essence of the Vedas” suggests the Upanishadic teachings. In verse 62 of the same chapter, Vyāsa says, “It (the Mahābhārata) has my explanations of the mystery of the Vedas, their Angās, and the Upanishads.” We see many more such assertions within the Mahābhārata that the author’s purpose was to present the Vedic wisdom in the epic’s backdrop.

We know none other than the Sage himself compiled the Vedas in the form they are available today. He then also had the perfect awareness that the seekers of wealth, pleasure and heaven used the Karma-Kānḍa* of the Vedas as the means to gratify their irrepressible material desires (kāma). The hankering for sensual pleasures and comforts and wealth had already brought about moral degeneracy (adharma) in the world. Therefore, we see in the epic that the poet revalues the Karma-Kānḍa practices and underscores the Vedantic import they suggest. He translates those revalued Vedic conceptions as the Vedantic means for the seekers of Truth. The Sage, by doing so, adopts a style that does not outright deny the widespread practices entrenched in the way of life during his time. Employing scrupulous attention to the existing conceptions, Vyāsa fits the defining ones with their fresh value in Brahma-vidya. The foremost example of such a revaluation is how he employs the yajña concept in Brahma-vidya to interpret Karma Yoga with complete clarity. [Yajña (fire-sacrifice) is the main ritual performed following the Karma-Kānda of the Vedas. The Gita does not encourage any such rituals for worldly gains.] The full, revalued conceptions he then presents in the final doctrine of the Bhagavad Gita. Further, the Sage employs the story-telling approach to make the Upanishadic philosophy intelligible and agreeable to more people of diverse temperaments. Direct admonitions quoting the Upanishads were perhaps ineffective to influence the nation in an era when wisdom held little attraction for people. We could thus infer that the epic was the Ṛshi’s strategic vision to re-establish righteousness (dharma).

[1The full name of Vyāsa who wrote the Mahābhārata.]

[*The Vedas are four–Ṛg Veda, Yajur Veda, Sāma Veda and Atharva Veda. Further, each of the Vedas has sections named the Samhitas, the Brāhmaṇas, the Āranyakas and the Upanishads. Appreciation of the cosmic beauty and praising of the forces of nature are part of the Samhitas. The Brāhmaṇas have the descriptions of transactional life and the associated Vedic rituals. Karma-Kānḍa refers to the Brāhmaṇas; the word Karma here means Vedic rituals such as yajña (fire sacrifice). The Āranyakas suggest the modes of worship and spiritual practices; and finally the Upanishads carry out scientific discussions on the fundamental questions of philosophical inquiry. Here, we can immediately see the sequential evolution of knowledge, starting with the observation of nature and ending up in discovering the secret of existence! “The cosmology of the Upanishads, which began with the worship of the phenomenal gods of the Vedas, found maturity in the course of the history of thought and arrived at wisdom having its centre in the Self of man. The Self was finally equated to the Absolute and spoken of as a supreme value referred to as Ānanda (Supreme Happiness).”]

The Thrust to Restate the Upanishadic Wisdom

What prompted Vyāsa to restate the Upanishadic wisdom through a work of art such as the Mahābhārata? He must have been the witness to a time in the history of ancient India when the age-old righteous way of ruling the nation disappeared altogether. In the Upanishadic period, kings had the dharma born of Brahman as the basis for governance. The evidence is in the Bhagavad Gita itself. Vyāsa says through Kṛshṇa, “Arjuna, the Yoga (the wisdom of yoga śastra) I am teaching you is the Yoga that has always existed. Your ancient ancestors who were rājarshis (king-sages) transmitted without fail the same yoga śastra from generation to generation. Alas, that yoga (and its influence in the world) has been lost for a long period now!” [The Bhagavad Gita IV.1 & IV.2.] Kṛshṇa cites the disappearance of the yogic way of life as the reason for the moral degeneracy (adharma) in the world. To save the world, the author of the Mahābhārata intends to restore yoga śastra or Brahma-vidya.

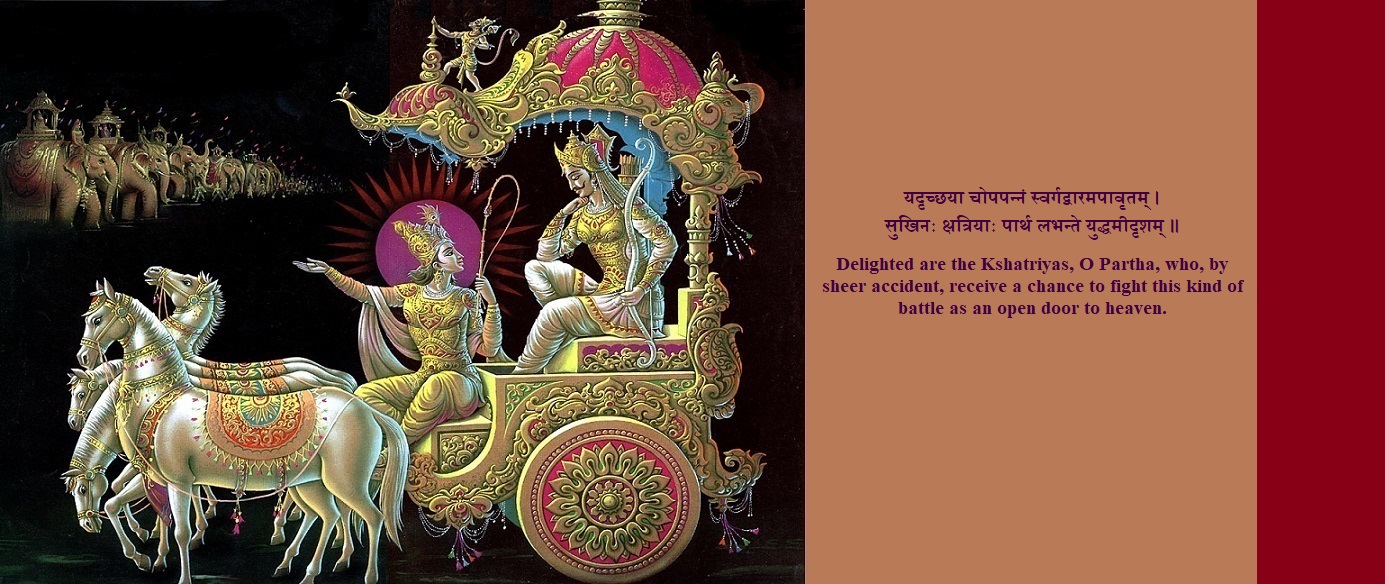

In ancient India, the profound philosophy of Brahma-vidya (Vedanta) was the foundation for the ruling kings. The foremost dharma (functional responsibility) of the king (Kshatriya) was to ensure the happiness and satisfaction of the citizens of the country. The king should have no other life interests above that dharma. He could have his own family life, but the interests of the citizens should always be above the family interests. Adhering to the dharma of a king, many rulers volunteered to lead the life of a sannyasin. They renounced pleasures of sensory stimuli; freed themselves from desires (kāma). As the Gita quote clarifies, in those days, kings lived as sages, so people called them rājarshis, king-sages.

Whenever the influence of the said philosophy (yoga śastra) weakened, the king and his descendants deviated from the tradition. They led a life that was far from a king’s dharma (functional responsibilities). Vyāsa witnessed this happening in the Kuru dynasty, where, in a crisis, he had to sustain the dynasty with his own progeny. The decadence of dharma and values had begun before his entry. And the ill fate of the dynasty worsened when the Sage’s descendants ruled the kingdom. Later, it culminated in an utterly disastrous battle between two branches of his descendants. We may thus call Mahābhārata Vyāsa’s own story.

The genius of Vyāsa would have embellished the historical elements not only to suit such a mammoth work of art but also to hammer the Upanishadic wisdom into the people of different temperaments and levels of intelligence.

[What is the motivation for a king to renounce all sensual pleasures and material comforts for the sake of the nation? People leading ordinary life may not understand it so easily, unless they know the philosophy we are about to learn. To answer in a word, a rājarshi is a knower of Brahman always experiencing the supreme value of being in the spiritual domain, so to him the worldly objects of enjoyment are of no interest. Later, we will understand it better listening to Kṛshṇa’s words.]

The message of the Mahābhārata to the world: Vedanta philosophy guides individual seekers of Liberation (moksha or mukti). The Upanishads declare that complete detachment from worldly gains is the only way to free oneself forever from the sorrows and sufferings that appear inescapable. Presenting the same philosophy in the epic, the author demonstrates the unique means to ensure the total well-being of the world. Vyāsa has set the teaching of the doctrine of paramount importance in human life in a dramatic scene, the rarest of its kind. He chooses the battlefield as the location to instruct a Kshatriya (ruler) in yoga śastra. It is not without a purpose. We have seen the prime dharma of a Kshatriya is to ensure the comprehensive well-being of the world. The poet’s point is simple and logical; if the world has to be rescued, the ruler must be reformed. A ruler’s transformation as a knower of Brahman makes him a rājarshi. Then the world is saved, for the people will follow him. Such rulers will preserve the wisdom in the minds of people by regularly imparting it to every generation; and themselves showing how to live by it. Vyāsa envisions the supreme well-being of every individual by instituting a governance system run by a class of enlightened rulers; he calls them rājarshis. They will perpetuate the pursuit of yoga śastra. To get across this message, the poet illustrates in the Mahābhārata what happens to the world when the rulers altogether neglect this philosophy (yoga śāstra or Brahma-vidya). He illustrates that acts of adharma (unrighteousness) are rampant in the nation; and presents a striking picture of the world that could not discriminate between dharma and adharma. We note that the time when the Sage lived was when, among the rulers, there were no more rājarshis.

So we should understand that the purpose of writing the Mahābhārata is not different from that of the Bhagavad Gita. In composing the epic with the Gita as its core, the Sage achieves the graphic presentation of a theme of universal importance. The theme: Jñāna is the means to make loka-samgraha a reality. [Jñāna: a liberated person’s knowledge of Brahman. Loka-samgraha: integral well-being of the world.] Without understanding this, all debates will happen on the periphery of Vyāsa’s principal theme.

The Rāmāyana and the Mahābhārata, considered epics, are called Itihāsas in India. By definition, an Itihāsa is the form of composition that has historical elements amply embellished by fictional and mythological characters and narratives. Its sole purpose is to enlighten the readers on the ideal way of life (dharma) that leads to jñāna. Jñāna brings perfect peace and happiness. Although they present contrasting narratives, both the Itihāsas have yet another significant common aim. It is to highlight the importance of jñāna to the ruler of a nation; or, to exemplify that only liberated rulers can accomplish the total well-being of the world (loka-samgraha). And such a ruler’s dharma (functional responsibility) is Kshatriya Dharma. [A Kshatriya’s dharma is often, owing to oversight, equated to a warrior’s job of fighting battles!]

Seen from this angle, the Bhagavad Gita addresses both an individual and the head of a state. The author has a Kshatriya (Arjuna) as the disciple to represent both. The Gita gives the Kshatriya, as an individual, the opportunity to gain Liberation through the supreme wisdom. In parallel, it insists that the knowledge of Brahman (jñāna) is vital for a ruler to the fulfilling of Kshatriya Dharma. Soon will we learn that becoming a jñāni too is a dharma (function) of a Kshatriya. For our svādhyāya to be effective, we must draw from the epic a thorough understanding of the relevance of jñāna to a ruler. If not, we cannot gain full clarity on Vyāsa’s goal of loka-samgraha through yoga śāstra.

An immediate hard task, therefore, is to present a summary of the Mahābhārata in a few pages, as the first step. Since Upanishadic wisdom is the theme of the epic, to perform this task without losing the soul of the composition is an insuperable challenge. Yet we will make a quick and simple outline of the story. It helps the readers with the exact context in which the teaching of the Gita takes place. Without understanding the setting Vyāsa has conceived to teach the Science of the Absolute, our spiritual journey will appear to be bumpy.

The main story of the Mahābhārata is that of the two branches (the Pāṇḍavas and the Kauravas) of the Kuru dynasty, of the circumstances which led to a battle between them for the throne, then of the battle itself, and further of the aftermath of the fierce battle. The Kuru dynasty was perhaps a powerful one then in the Indian subcontinent. Vyāsa has enhanced the main plot with many, many sub-plots and philosophical discourses to include a complete treatment of the Vedic vision.

The Sage accomplishes the exposition of the Vedanta philosophy by presenting mythological as well as worldly characters from the three worlds popular in the Vedic tradition. The Sage himself is a character in the epic. He describes his birth and the crucial role he plays in the early stages of the story when the Kuru dynasty was on the verge of extinction for want of descendants. Later he appears at critical junctures, often in the scenes that call for his yogic vision to explain matters which are out of the ordinary. It is the longest2 poetic work ever composed, the importance of which is no less than that of the Vedas.

[2Over one hundred thousand verses in the Sanskrit language.]

[Vyāsa exposes the life of moral depravity human beings resort to when they do not anymore practice dhārmic way of life. Dhārmic way of life is adherence to yoga śastra. It is for us to relate the principles we learn to our own lives and the socio-political situations we encounter in the world every day.]

The Mahābhārata‒A Short Summary

Vyāsa’s Origin

In the vicinity of Hastinapura, the seat of the Kuru Kingdom, Sage Parāśara met a damsel of unmatched beauty by the name of Satyavati, the ferrywoman who should take him across the river. Her father was the chieftain of the fishermen community. Parāśara’s awe-inspiring, radiant figure and his mystic aura aroused in Satyavati a fervent, uncontrollable desire for union with the Sage. She quietly greeted him with a demure smile, when the Sage saw a flash of burning passion in her eyes, aflame with love.

The ferry reached the middle of the river with no other fellow passengers, and Satyavati was in the middle of her private dreams. Suddenly Parāśara asked her whether they should now consummate their love. The Sage, with his mystic power, created a veil of fog around them and saved her from any embarrassment. To Satyavati’s delight, the union she desired thus materialized. Parāśara then continued with his pilgrimage from the other side of the river.

In the style of any mythical tale, Satyavati instantaneously gave birth to Vyāsa who, with his mother’s consent, renounced the regular householders’ life and went away to become a sage himself. Satyavati had the blessings of Parāśara to remain a virgin. The entire affair so remained a well-kept secret.

[Vyāsa narrates, without glorifying, the story of his origin, which may sound like a licentious affair at any point in history. Yet he depicts the story in this fashion, particularly because it involves a sage, Parāśara, who was a seeker of the highest order, committed his life to pursue the path of the Supreme. Vyāsa demonstrates to the world that even a sage of Parāśara’s stature, whom the world could never expect to act as he did in this episode, could fall prey to the instinctive emotions of an ordinary human being. The striking greatness of such individuals as Parāśara is that they regain from such falls immediately and with greater determination continue with their life’s goal to attain the Ultimate.]

King Śantanu of the Kuru Dynasty

King Śantanu of Hastinapura was married to Ganga (the river Ganges personified), of celestial beauty. Ganga had agreed to marry Śantanu on the condition that he would never question her decisions and actions. He lived a life of absolute carnal pleasure, which Ganga was capable of and willing to treat him with. She gave birth to seven children whom she promptly drowned in the river Ganges on the day each one was born. Śantanu was shocked, but he remained silent. Inside him, dissension was brewing gradually, but he struggled to hide it for the fear of losing Ganga, who was to him the abode of pleasure.

The eighth son was born to the couple when Śantanu could no longer resist his urge to protest. He objected to the child’s drowning and, on his violation of the mutual agreement, Ganga decided to part. She, however, took the child named Devavrata along with her with no hesitation; several years later she brought him back to Śantanu. Before bringing him back, Ganga had ensured that Devavrata, now a grown-up gallant prince, gained mastery in all branches of knowledge, archery, and warfare under the tutelage of Sage Vasishtha, Sage Śukra, and Paraśurāma.

Śantanu, the king of kings, was now old when the concomitant infirmities began showing themselves on his body. His hankering for sensual pleasures remained unbridled. He fell in love with a gorgeous young woman, Satyavati, the spellbinding fragrance of whose body not only announced her presence but also allured even an indifferent passerby. Her father, the chieftain of the fishermen community, was ready to accept Śantanu’s proposal to marry her only on the condition that Satyavati’s son should inherit the throne of Hastinapura. For fear of causing injustice to Prince Devavrata, Śantanu backed out of his proposal.

The intelligent prince found out the cause of his father’s gloomy disposition, rode over to the chief of fishermen, and made two vows: one, that he would never claim the throne of Hastinapura, and two, that he would remain all his life a celibate so that he would have no progeny to claim the throne either. Seeing Satyavati being brought to the palace, King Śantanu was so overwhelmed by his affection for his son that he granted Devavrata the boon of swacchanda mṛtyu (to die only when he desired). The audacious vows that Devavrata had taken earned him the name Bhīshma.

Śantanu and Satyavati had two sons, Chitrāṅgada and Vichitravīrya. The king did not live long enough to hand over the throne to one of Satyavati’s sons. After the king’s death, Bhīshma made young Chitrāṅgada the king, who later annexed many princely states in the neighborhoods and displayed his valor. The conceited young king met with his end when he challenged and fought with a gandharva (celestial beings known for their music and other talents) of the same name, Chitrāṅgada. Bhīshma then with all his blessings installed Vichitravīrya as king of Hastinapura. By then, Vichitravīrya had contracted tuberculosis because of his immoderate life of indulgence.

Having learned about the svayamvara3 ceremony of the three princesses of a neighboring kingdom, Bhīshma went there and took away the princesses by brute force, in front of all the other princes and kings present at the ceremony. He wanted the ailing Vichitravīrya to marry all three. The eldest of the three princesses, Amba, was in love with Sālva, the king of Saubala. Sālva resisted the insolent act of capturing the princesses from the svayamvara hall, but Bhīshma defeated and humiliated him. Although Amba could argue with Bhīshma and free herself, the disgraced Sālva refused to marry her. She came back and insisted on Bhīshma that he should marry her since he had ruined her love, but he stood firm by his vow to remain a celibate.

Burning with the desire to wreak vengeance, Amba did penance and propitiated the god Śiva who blessed her that in her next birth, she would become the reason for Bhīshma’s death. She was born as a daughter of King Drupada and later she practised austerities and transformed herself into a man named Śikhandin.

Vichitravīrya married the other two princesses–Ambika and Ambālika–but, suffering from tuberculosis, he neither lived long nor left an heir in the Kuru dynasty. Overwhelmed by the injustice of it all, the vengeful princesses could never forgive Hastinapura, for every consequence they faced helped only to provoke their full wrath.

[3Svayamvara: A royal ceremony for a princess to marry usually the winner of a challenging contest that the king decides upon. The princess’s choice/decision was final.]

The Kuru Dynasty on the Verge of Extinction

Satyavati did not succeed in persuading the unyielding Bhīshma, who stuck to his vows, to take charge of the Kingdom. She then summoned her son Vyāsa and asked him to impregnate the two princesses so that the Kuru dynasty would continue to exist. The prevailing law of the time allowed considering Vyāsa, the child born of unwed Satyavati, the stepchild of Śantanu. Thus, she could ask him to save the dynasty from extinction.

Sage Vyāsa acquiesced to his mother’s requirement. The Sage with his mystic powers foresaw the untoward consequences if he were to approach the princesses at once. He asked his mother to wait for a year to allow the princesses to mellow down and gain the right level of maturity in thinking. Satyavati rejected outright her son’s suggestion.

The two princesses, Ambika and Ambālika, had a son each of Vyāsa. Observing the implacable princesses and their behavior and attitude, Vyāsa had predicted that Ambika would have a blind son and Ambālika a son afflicted by a life-threatening type of anemia. They were the fruits of their unrelenting desire for revenge. Stricken with despair, Satyavati wished for another child of Vyāsa and Ambika, but Ambika did not agree to the proposition; instead, she sent her handmaid to Vyāsa. With full of devotion and love, the handmaid offered herself to the Sage, and she gave birth to a son who was of perfect health and intelligence, and later in life he became devoted to the observance of dharma (righteousness). The three sons were Dhṛtarāshṭra, Pāṇḍu, and Vidura respectively. Having fulfilled the requirement of Satyavati, Vyāsa retired to his life of penance (tapas). Bhīshma raised the three princes with great care and love. Dhṛtarāshṭra, despite being blind, grew up to be the strongest of all princes. Pāṇḍu became accomplished in warfare and archery, and Vidura gained mastery in all the branches of learning, politics, and statesmanship.

Although Dhṛtarāshṭra was the eldest, the law of the time prohibited a blind prince from ascending the throne. The lone choice was Pāṇḍu because Vidura, who was born of a handmaid, could neither qualify to be the king.

Again, Bhīshma himself took the lead in finding brides for Dhṛtarāshṭra, Pāṇḍu, and Vidura. Dhṛtarāshṭra married Gāndhāri, who decided to live with her eyes always covered with a piece of cloth tied behind her head–what her husband did not enjoy, she did not want to enjoy either! Pāṇḍu had two wives, Kunti of the Yādava clan, and Mādri, the princess of Mādra kingdom. Vidura’s bride, the daughter of King Devaka, was of admirable qualities.

Pāṇḍu expanded the kingdom by conquering all the other kingdoms of the surrounding region and brought in immense wealth as war booty. With the affairs of the kingdom running unchallenged, and with its coffers full, King Pāṇḍu temporarily retired to the forests along with his wives, Kunti and Mādri, asking his elder brother Dhṛtarāshṭra to look after the state matters until he returned.

The Kuru Princes are Born and King Pāṇḍu Departs

In the forests, Pāṇḍu and his wives were enjoying the long-awaited break. Then, like a thunderbolt, came a deadly curse upon the King. Pāṇḍu was out on his hunting sport and he shot a male deer of a pair engaged in love. The dying deer cursed the King, saying that he had done an unforgivable sin and so he would also meet his end in the act of lovemaking. The deer was Kindama, a sage in disguise.

The repentant Pāṇḍu, along with Kunti and Mādri, decided to lead a life of penance (tapas) in the forests and sent a message to Hastinapura about their intention not to return. Although he could reconcile himself with the fate, the King’s greatest worry was that he did not have any sons to perform his last rites following the tradition. He tried hard to impress upon Kunti that there were lawful ways, as existed those days, for her to bear a child from another man, especially when in such a predicament. Kunti remained unyielding. She then remembered the blessing received in her childhood from Sage Durvāsā. Once, the Sage had visited her stepfather’s palace; pleased with her services as a courteous host, he had given her a divine mantra. Any god on whom she was to meditate by chanting the mantra would appear before her and give her a son. Hearing about it, Pāṇḍu was thrilled, and he persuaded Kunti to act in haste. She invoked Lord Dharma (Dharmdeva). With the Lord’s blessings, she became pregnant and, in time, she gave birth to Yudhishṭhira. Pāṇḍu kept asking for more children. She agreed for two more and gave birth to Bhīma of Lord Vāyu (Vāyudeva) and Arjuna of Lord Indra. When asked again, Kunti refused, but she chanted the mantra for Mādri who, with the blessings of Ashwinī devās, became the mother of the twins, Nakula and Sahadeva.

Long ago Kunti had received the divine mantra, by the power of which the five Pāṇḍava children were born. It was well before she became an adult, when she had not understood its significance. The young lass had been curious to know what would happen if she had chanted the mantra. She had prayed to Sūrya-deva (the Sun god) and chanted the mantra. Lo! To Kunti’s embarrassment, Sūrya-deva had instantly appeared before her. Although she had profusely apologized to the god and begged him to forgive her, the intended purpose of invoking the god using the mantra had to be fulfilled, and Kunti had given birth to a child of distinguishing features. Sūrya-deva had blessed she would remain a virgin and disappeared. The unwed mother could abandon the child the very night, attracting nobody’s attention. The abandoned child had reached safely in the hands of the sūta (charioteer), by the name of Adhiratha, of the Kuru Kingdom, and he had happily raised the child who came to be known as Karna.

A year after the birth of Yudhishṭhira, in Hastinapura, Gāndhāri gave birth to one hundred sons and a daughter. Duryodhana was the eldest. The lone daughter was Duśśala. Dhṛtarāshṭra was exhilarated at the birth of his sons. When Duryodhana was born, nature was replete with terrible omens. The learned men like Vidura and other pundits were of the view that if Dhṛtarāshṭra sacrificed this child, he would save the world from grave peril. Dhṛtarāshṭra was so fond of his son that he paid no heed to the words of the wise.

In the forests, Pāṇḍu’s joy knew no bounds; the extremely gratified King rejoiced at the birth of the five sons of divine origin. One day, in the salubrious, inspiring ambience of the forest and the charming lone presence of his gorgeous wife Mādri, Pāṇḍu lost himself in the luring depths of conjugal love and never returned.

Mādri sacrificed her life in Pāṇḍu’s funeral pyre as a mark of her absolute devotion to her beloved. Kunti had wanted to act the same way, but Mādri had implored her to stay alive, for she had wanted all the five little children to be looked after with the undivided love and care of a mother that Kunti alone could ensure. The five sons of Pāṇḍu and their mother, Kunti, returned to Hastinapura, and they received a warm welcome in the palace.

The Kauravas and the Pāṇḍavas

The sons of Dhṛtarāshṭra, Duryodhana and his siblings, were addressed as Kauravas, the members of the Kuru dynasty, whereas the sons of King Pāṇḍu, indeed of the same dynasty, carried their patronymic title, the Pāṇḍavas. Duryodhana and Bhīma were born on the same day in two different places. Yudhishṭhira, born a year before, was the oldest among both the Kauravas and the Pāṇḍavas.

The palace appointed Kṛpāchārya (Kṛpa the teacher) to teach the one hundred and five princes Dhanurveda (the science of archery) and other branches of learning. Later, an exceptionally gifted Dhanurveda teacher by the name of Droṇā arrived in the palace who impressed the princes with his mastery. Bhīshma, the grand mentor and patriarch of the Kuru family, entrusted Droṇāchārya with the task of training the princes in Dhanurveda and the art of war to become accomplished warriors.

The Pāṇḍavas proved, in Droṇā’s classes, to be quicker in learning and more talented than the Kauravas. Arjuna, the third among the Pāṇḍavas, came out to be the finest in archery and, in no time, he became the most favorite student of Droṇā. Bhīma and Duryodhana were specializing in mace-fight. The former, the second Pāṇḍava prince, was far greater in talent and physical strength. His practical jokes not only irked but also hurt the ego of Duryodhana and his younger brothers. The Pāṇḍavas often defeated the sons of Dhṛtarāshṭra in the mock-games in the classes, so the Kauravas became jealous out of an inferiority complex, which over time turned out to be vengeance and animosity.

Dhṛtarāshṭra, the continuing ruler-in-charge after the death of King Pāṇḍu, was extremely fond of his eldest son, Duryodhana. The blind greedy king-in-charge nurtured a secret dream that one day his son would be on the throne of Hastinapura, which in reality belonged to King Pāṇḍu after whose death his eldest son Yudhishṭhira (the oldest among the Kauravas and the Pāṇḍavas too) should inherit. The entire world was waiting to see Yudhishṭhira installed on the throne, when he would complete his education.

Prince Duryodhana, even as a child, was conscious that his father’s affection for him was deep and special. At an early age, he also realized he could get away with any mischiefs because his father, the ruler-in-charge, held absolute power in the kingdom. He always used the indulgence he enjoyed wreaking vengeance on the Pāṇḍavas, more often on his counterpart, Bhīma, in the chosen areas of specialized training. He dared to poison him, not once, but twice. But Bhīma survived both attempts. In contrast, the Pāṇḍavas were tolerant and honest; having been of divine origin, they were virtuous by nature. As the princes were completing their training, under Droṇā and Kṛpa, in Dhanurveda and other śāstras (branches of learning), the hostility of the Kauravas towards their cousins also hardened, to remain irreversible forever.

No sooner all princes completed their schooling than the Kuru elders held a public show of the skills they had mastered. In that event, the citizens came to know that the Kauravas were full of hatred and bitterness for their cousins, the Pāṇḍavas. In the grand show of war skills, Arjuna presented a magnificent performance at archery. Duryodhana and Bhīma had a mace-fight, which had to be stopped before it turned ugly. Karna, an uninvited non-Kuru, with a flamboyant personality that amazed the cheering spectators, entered the scene and displayed his talent in archery. It proved to be a notch above that of Arjuna. Duryodhana seized the opportunity to secure Karna by his side and to declare him his bosom friend. When Karna challenged Arjuna for single combat, Duryodhana was in a jubilant mood to see a gallant warrior who could take on the invincible Arjuna. Kṛpa, erudite in the rules of war games, was quick enough to intervene and ask Karna to speak about himself and his ancestry before he could qualify himself to challenge a prince such as Arjuna. Kunti fainted at the sight of her two sons challenging each other as hated enemies. The highlight of the show was that Duryodhana won Karna over forever as he made him, on the spot, the king of a vassal state, Anga, to qualify him for the single combat with Arjuna. Bhīma then grabbed the opportunity to disparage Karna by highlighting his non-royal origin. And the show came to an abrupt end.

Questions came up from different quarters on Dhṛtarāshṭra’s occupying the throne, with no signs of transfer of power. He became the ruler-in-charge in the interim, only by delegation. The blind king did not find any plausible reason to go against Yudhishthira’s natural claim on the throne, for he was not only the eldest son of King Pāṇḍu, but the oldest among the Kuru princes. Besides, Yudhishṭhira was famous among the citizens as the most virtuous of all the one hundred and five princes and that he always stood unswerving on the side of dharma (righteousness). Yielding to the unanimous view of the elders and the gurus (such as Droṇā and Kṛpa) of the Kuru family, a helpless Dhṛtarāshṭra in a royal ceremony declared Yudhishṭhira the crown prince.

The Pāṇḍavas in Vāraṇāvata

Duryodhana was at his wit’s end when he witnessed the investiture of Yudhishṭhira as the crown prince. His restless mind had only one thought: I must do away with the Pāṇḍavas and secure the kingdom for myself. Yudhishṭhira, known for his staunch adherence to dharma (righteousness), was already very popular with the citizens. The virtuous Pāṇḍavas commanded the love and respect of everybody. Duryodhana, in his exasperation, sought the help of Karna and his maternal uncle, Śakuni, a master in scheming and crafting devious plans. Together they made a treacherous plan to send the Pāṇḍavas away to a remote town called Vāraṇāvata and exterminate them when they were away from Hastinapura. Dhṛtarāshṭra feared the wrath of not only the Kuru elders, but that of the citizens as well. When Duryodhana explained how he already manipulated to garner enough support through bribery and undue favors, he saw a smile of admiration that flashed on his blind father’s face. Dhṛtarāshṭra’s youngest brother, Vidura, was the one who stood for dharma. As the prime minister to Dhṛtarāshṭra, Vidura had to keep quiet and obey the orders. Dhṛtarāshṭra thus advised the Pāṇḍavas to proceed, along with their mother Kunti, to Vāraṇāvata and to live there for a while to ensure the happiness of the citizens in that part of the kingdom.

The Pāṇḍavas agreed with pleasure to the fatherly advice of the King. Out of genuine affection for the Pāṇḍavas, Vidura spoke to Yudhishṭhira in absolute secrecy that Duryodhana planned to endanger their lives. The palace at Vāraṇāvata was made of special flammable materials such as wax and fiber, but finished with meticulous perfection to look safe and sound. Once the Pāṇḍavas settled in the palace, one of Duryodhana’s agents would set the wax-palace on fire. Having understood the enormity of the crime being conspired, Bhīma boiled inside and regretted that he could not give Duryodhana a fitting reply.

Vidura arranged with his loyal men to dig a tunnel beneath the palace at Vāraṇāvata for the Pāṇḍavas to escape in an emergency without attracting the attention of Duryodhana’s men. At Vāraṇāvata, the Pāṇḍavas hosted a feast to the brāhmaṇas in the region. An old woman and her five sons, of a forest tribe, who lived on alms, were too drowsy to leave the palace after the sumptuous feast, so they spent the night in the palace hall. The same night, the Pāṇḍavas themselves set fire to the palace and escaped through the tunnel. When the fire went out, the people of Vāraṇāvata found among the debris the unrecognizable mortal remains of a mother and five young men. They wept and wailed for the worthy Pāṇḍavas and their mother Kunti, and were vexed at the villainous act of Duryodhana, well supported by the unscrupulous blind King.

Duryodhana thanked his uncle, Śakuni, for his skillful plan and its flawless execution; he heaved a sigh of relief, as the throne of Hastinapura now remained unchallenged for him to occupy.

The story is concluded in the NEXT POST.

----------------------

(To read the next post [Gita Post #2], click/tap on this link: The Mahābhārata story-Part II)

Comments (6)

Good, Proceed ..

Namaste!

When I try to browse to the next section by clicking on the page indices given at the bottom, it comes back to this same section only. Please look into it and correct

Thank you. The problem is now corrected. Namaste!

This is exactly the kind of introduction or the context setting I was looking for and believe me I have perused many books but wasn't satisfied. This blog is the best in doing that. Also I think I have figured out how to traverse nodes in reverse order to go sequentially per Gita chapters :-)

Thanks, Nitin. It is good to hear that the effort is worth putting, that is, if it genuinely helps somebody in his/her quest. Namaste!

Leave a comment